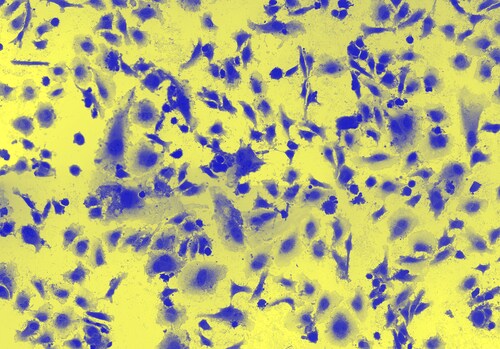

Biospecimen research has made, and continues to make, significant contributions to new understandings of human biology. It has contributed to targeted approaches to detecting and treating health conditions, as well as reducing the risk of future disease. The long-term success of biospecimen research depends on addressing concerns such as informed consent, oversight by institutional review boards, large-scale data sharing, privacy and confidentiality, commercialization, access to research results, and the ability to withdraw. The story of Henrietta Lacks highlights the need for governance in biobanking. In exploring this issue, Beskow (2016) draws on Lacks’s story and how the now commonly known HeLa cells were actually originally derived from her aggressive cervical cancer. In 1951, doctors removed tissue samples during Lacks’s diagnosis and treatment and passed them on to researchers, who produced the very first line of human cells grown outside the human body. However, Lacks and her family were unaware that her tissue was used in this way. The subsequent discovery that this had taken place prompted important discussions about consent and privacy.

Biospecimen research has made, and continues to make, significant contributions to new understandings of human biology. It has contributed to targeted approaches to detecting and treating health conditions, as well as reducing the risk of future disease. The long-term success of biospecimen research depends on addressing concerns such as informed consent, oversight by institutional review boards, large-scale data sharing, privacy and confidentiality, commercialization, access to research results, and the ability to withdraw. The story of Henrietta Lacks highlights the need for governance in biobanking. In exploring this issue, Beskow (2016) draws on Lacks’s story and how the now commonly known HeLa cells were actually originally derived from her aggressive cervical cancer. In 1951, doctors removed tissue samples during Lacks’s diagnosis and treatment and passed them on to researchers, who produced the very first line of human cells grown outside the human body. However, Lacks and her family were unaware that her tissue was used in this way. The subsequent discovery that this had taken place prompted important discussions about consent and privacy.

One particular consequence of researchers creating HeLa cell lines is that the data provided probabilistic information about Henrietta and her descendants that became known to millions, and thus raised concerns regarding her privacy. In response, in 2013, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) met with the Lacks family, and they agreed that the data would be placed in a controlled-access database. The applications to study this data are reviewed by a committee that includes members of the Lacks family.

What does this mean for consent processes now? Actual consent practice varies, as biobanks are highly heterogeneous in terms of tissue type, procurement situation, and geographic, social, and historical context. Furthermore, regulations and guidelines concerning informed consent are not necessarily specific to biospecimen research, nor are they harmonized. Current U.S. regulations (known as the Common Rule) were developed in response to revelations of extreme research abuses in vulnerable populations; these regulations were designed primarily to protect human beings from risks involved in experimental research. The Common Rule defines a human subject as a living individual about whom an investigator obtains (a) data through intervention or interaction with the individual or (b) identifiable private information. Thus, when an investigator interacts with a person to collect biospecimens specifically for research, informed consent is required. Furthermore, a fundamental strategy to protect confidentiality is to remove direct identifiers and replace them with a code, and take additional steps to ensure that researchers have no access to identifying information.

In September 2015, the federal government published a notice of proposed rulemaking to overhaul the Common Rule. Among the most significant changes are those proposed for biospecimen research:

- The definition of a human subject would be modified to include living individuals about whom an investigator “obtains, uses, studies or analyzes biospecimens” regardless of identifiability.

- Consent would be required for research use of all biospecimens, regardless of whether they were originally collected for research, clinical or other purposes and whether they are de-identified (notably, consent would not be required for secondary research use of non identified private information, such as medical records).

- Consent would not be needed for each specific study, but rather could be obtained through broad consent for future unspecified research.

- The government would develop a broad consent template covering the storage of biospecimens and data for secondary research, as well as the use of stored materials for specific studies.

- Additional consent elements would cover commercial use and profit from study of biospecimens, return of individual research results, optional recontact and widespread sharing.

- Use of secondary biospecimens to establish a biobank would be exempt from the regulations, subject only to limited institutional review board (IRB) review to ensure that initial broad consent and specified privacy and security safeguards are in place.

- Research using materials that have been stored for secondary use would be exempt from the regulations and required only to have safeguards in place (with no IRB review).

Beskow concludes by saying that informed consent is challenging. Research shows that consent forms are too long and written at too high a grade level, and most participants do not completely understand the process. Furthermore, interventions to improve participant understanding and informed consent processed have not been successful. Although Henrietta Lacks’s story occurred long before development of informed consent processes, it highlights the need for collaboration, not just within the scientific community, but also with the broader community, in order for biospecimen research to remain a significant contributor to medical discoveries.

Reference

Beskow, L.M. (2016) “Lessons from HeLa Cells: The ethics and policy of biospecimens,” Annual Reviews in Genomics and Human Genetics [Epub ahead of print].

Leave a Reply