Although bacteria are the major cause of microbial foodborne illness, consumers and producers alike still need to be aware that viruses including hepatitis A are a source of disease. Disease surveillance in the United Kingdom found that during 2009, 18% of all cases of foodborne illness came from ingestion of viruses in food, with hepatitis A being a notable risk.

Although bacteria are the major cause of microbial foodborne illness, consumers and producers alike still need to be aware that viruses including hepatitis A are a source of disease. Disease surveillance in the United Kingdom found that during 2009, 18% of all cases of foodborne illness came from ingestion of viruses in food, with hepatitis A being a notable risk.

Hepatitis A

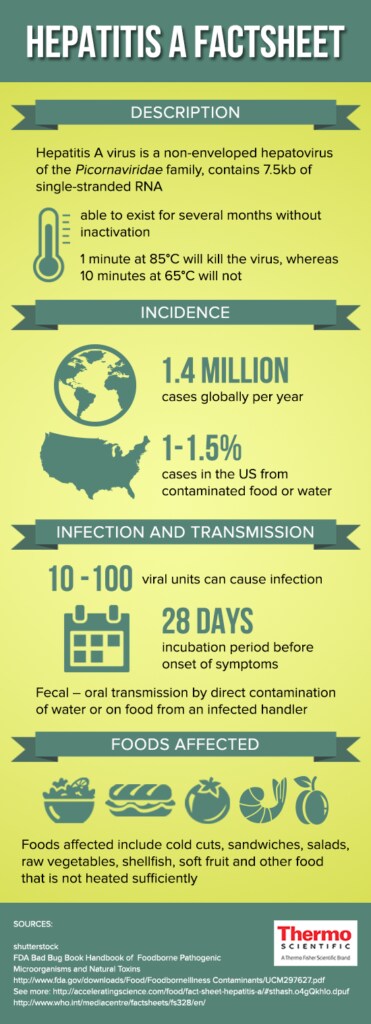

Hepatitis A, one of five different hepatitis viruses, is a non-enveloped hepatovirus and member of the Picornaviridae family. It contains 7.5kb of genomic material in the form of single-stranded RNA. Hepatitis A virus (HAV) is found in a wide range of primate species and humans. Infection is usually by the oral route, where consumers take in virus particles shed in feces from infected individuals.

HAV is a resilient virus, able to exist in soil and other environmental conditions for several months without inactivation. It is not inactivated by desiccation if sufficiently protected in environmental fomites, and it is likewise unaffected by acid. Although it does not multiply within foods, it can remain infective for up to five days at 4°C or room temperature. Heat inactivation at the right temperature is possible – 1 minute at 85°C will kill the virus, whereas 10 minutes at 65°C will not.

Incidence

Industrial countries report a decrease in HAV infections annually, though there is cyclical incidence of the disease through time. In the United States, between 1% and 1.5% of all HAV cases reported arise from contaminated food or water. According to the Center for Disease Control, in 2013 12.8% of cases with sufficient information about linkage to an outbreak indicated the source could be water- or foodborne.

HAV infection is also of low incidence in Europe; however, in 2013 disease monitoring by the Epidemic Intelligence Information System for Food- and Water-borne diseases (EPIS-FWD) of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) recorded three large outbreaks associated with consumption of contaminated berries.

In Canada, 2006 reports show hepatitis A responsible for 0.02% of all recorded cases of foodborne illness in that year1.

Infection and Transmission

Once a sufficient dose has been ingested (thought to be between 10 and 100 viral units), there is an average of 28 days incubation period before onset of symptoms. During this time, the infected individual sheds HAV from the gastrointestinal tract.

In children, the disease may go unrecognized with mild or no symptoms at all. In adults, there is usually acute hepatitis and fever at first, which then breaks with the development of icterus or jaundice seen as yellowing of mucous membranes. The course of the illness once noticed runs around eight days. Few cases develop liver failure, which is seen in 0.3 – 1.8% of cases, and usually confined to older adults.

While the disease is developing, the virus actively sheds from the gastrointestinal tract. Unfortunately, the long and symptomless incubation period can extend between three and six weeks, thus increasing the risk of contamination since the patient is unaware of their condition. Fecal transmission is the most common route for passing on HAV infection, with either direct contamination of water systems through sewage or on food from an infected handler.

Foods Affected

HAV infection in industrial countries usually comes from eating contaminated foods. There is therefore an obligation on the part of the food industry to minimize exposure through safe practices and good hygiene.

Although cases arise from eating shellfish already infected with HAV though cultivation in contaminated water, the majority of foodborne HAV cases come from contamination by an infected individual handling the foods. Foods affected include cold cuts and sandwiches, salads and raw vegetables, and any other food that is not heated sufficiently post handling by an infected person.

Avoiding food contamination requires strict attention to hygiene and safe preparation procedures by food industry workers. Vaccination is available but has not been recommended routinely for workers in the industry, unless required for post-exposure prophylaxis.

Learn more about ensuring food safety with solutions for foodborne virus testing

References

1. Thomas, M.K. et al. (2013) “Estimates of the Burden of Foodborne Illness in Canada for 30 Specified Pathogens and Unspecified Agents, Circa 2006”, Foodborne Pathogens and Disease 10 DOI: 10.1089/fpd.2012.1389

Further Reading

- FDA Bad Bug Book Handbook of Foodborne Pathogenic Microorganisms and Natural Toxins http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Food/FoodborneIllnessContaminants/UCM297627.pdf

- Advisory Committee on the Microbiological Safety of Food Ad hoc Group on Foodborne Viral Infections: An update on viruses in the food chain http://acmsf.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/acmsf-virus-report.pdf

- Chief Scientific Advisor’s Science Report Issue One: Foodborne Viruses https://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/csa-report-issue-one-foodborne-viruses.pdf

Leave a Reply