The Genome Trakr network, a United States–based whole genome sequencing (WGS) network, is described by Allard et al. (2016) as the nation’s food shield.1 The purpose of this open-source tool is to monitor foodborne disease (FBD) outbreaks as laboratories identify the pathogens responsible. Setting up a networked and open-access platform like this allows regulatory officials in public health food standards to track and quickly identify outbreaks before they become widespread. Since its inception, Genome Trakr has enabled a faster response for food safety recalls.

The Genome Trakr network, a United States–based whole genome sequencing (WGS) network, is described by Allard et al. (2016) as the nation’s food shield.1 The purpose of this open-source tool is to monitor foodborne disease (FBD) outbreaks as laboratories identify the pathogens responsible. Setting up a networked and open-access platform like this allows regulatory officials in public health food standards to track and quickly identify outbreaks before they become widespread. Since its inception, Genome Trakr has enabled a faster response for food safety recalls.

In the US, officials estimate the burden of FBD each year as costing around $152 billion, with 48 million cases, 128,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths. However, surveillance shows that a faster response as soon as agencies detect an outbreak reduces impact. For this reason, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) set up the Genome Trakr network in 2012 to monitor FBD outbreaks and enable faster identification of sources through WGS.

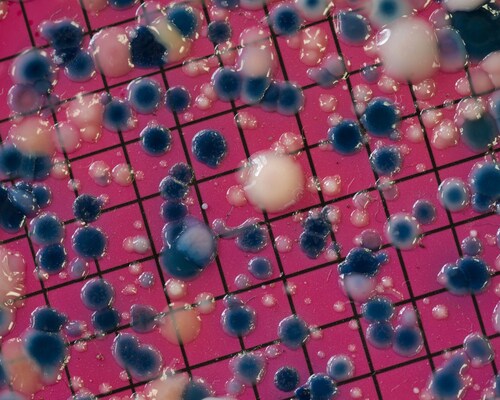

The Genome Trakr network started with four states and nine FDA field labs that collected WGS data on FBD pathogens submitted for public health. Once collected, the network made the WGS data publically accessible. Since then, the network expanded; it now covers 30 independent laboratories, which all use next-generation sequencing (NGS) for pathogen characterization. These include facilities within the US and also internationally. These partners add the pathogen data directly to the Genome Trakr databases. With this growth, the databases now hold WGS information on 33,000 Salmonella, 7,000 Listeria, 5,000 Escherichia coli and Shigella, and 1,000 Campylobacter isolates. The FDA estimates that the databases grow by 1,000 new draft genomes per month, or approximately one per hour.

There are two keys to the success of the network: centralization with global accessibility and rapid data uploads. The open data model allows agencies throughout the world to examine WGS data held on a large number of FBD pathogen isolates. These data are held in association with metadata such as geographic location, food type, brand and date information. Although there are privacy barriers for individual identifiers, the accessibility to such a comprehensive database allows global tracking and links to outbreaks and their sources worldwide.

Another reason behind the success of Genome Trakr is its use of NGS technology for WGS to replace traditional pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). Although PFGE was initially effective in identifying FBD pathogens, NGS is a much faster tool, better suited to automation and digital data uploads. Furthermore, WGS data can discriminate more effectively between isolates, which is important in confirming the source of the outbreak and implementing effective recalls.

Although the FDA first conceived the network as a way to manage FBD outbreaks, the information held now gives details on antimicrobial resistance, serological typing for antibody characterization, and virulence and pathogenicity assessment for emerging disease. Genome Trakr also seeks to encourage public health laboratories to move all their sequencing data online for maximum collaboration. For example, closer ties could help comparison between clinical and food samples during an outbreak.

As well as improving consumer safety with a more efficient and rapid response to outbreaks, Genome Trakr also supplies food industry members with useful information. WGS data highlight risk areas in food types and processing workflows that can help formulate robust good manufacturing practices (GMP) and support hazard analysis and critical control points (HACCP). These are both areas important to compliance with new Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) regulations.

Reference

1. Allard, M.W., et al. (2016) “Practical value of food pathogen traceability through building a whole-genome sequencing network and database,” Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 54(8) (pp.1975–83). doi: 10.1128/JCM.00081-16

Read more about monitoring FBD outbreaks on Examining Food

Leave a Reply