This is the next post in our immuno-oncology blog series. Start from the previous post here or follow along as we discuss the process for creating a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell.

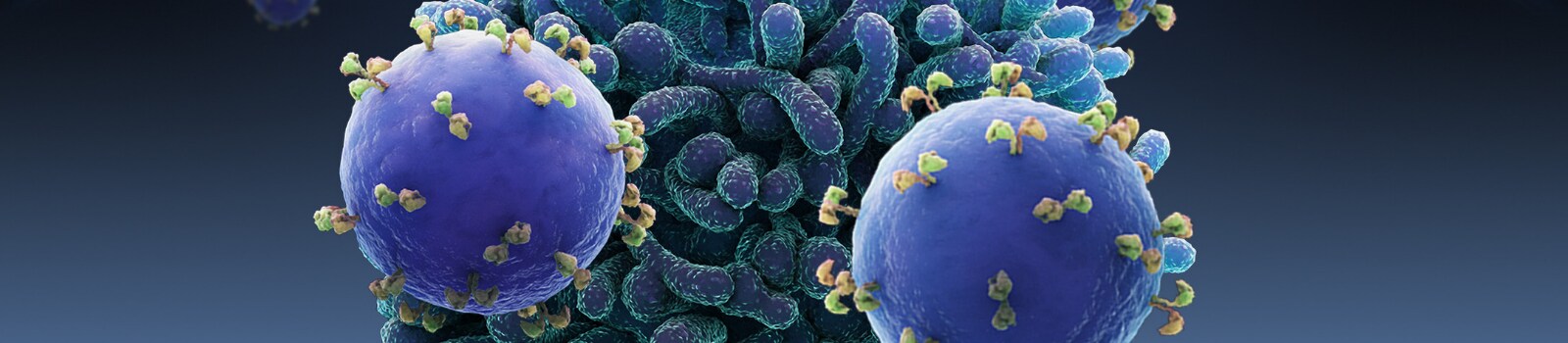

A CAR T cell is a T cell that targets, not an antigen presented by another part of the immune system, but something it has been genetically engineered to specifically attack. CAR T cell activity effectively replaces the natural targeting system based on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins with a human-made receptor that attacks whatever it has been designed to attack.

Creating a CAR T cell is an involved, multi-step process involving cell culture and gene editing over the course of weeks and even months.

The first step is to carefully examine the host’s cancer to identify one or more antigens that the chimeric cells can be engineered to target. This may involve a tumor biopsy or blood draw. Once B cells of human or mouse origin are exposed to this antigen, some of them will begin to produce antibodies against it. In monoclonal antibody therapy, these antibodies would be the treatment administered to the host, but in CAR T cell therapy, it is the cells producing those antibodies that are needed for the next step.

Figure 1. The process of creating a CAR T starts with collection of T cells (leukapheresis), which are then activated and transduced with the genetic sequence of interested, tested and expanded for expression.

At the same time, the host’s T cells must be collected. In a process called leukocyte apheresis, or leukapheresis, the host is given two simultaneous intravenous lines, or an equivalent venous central line apparatus. These lines are then used to draw blood, separate out its T cells, and return the rest to the host. It is sometimes necessary to provide the host with supplemental calcium during this process to prevent the short-term deficiency that the procedure can induce.

To create a CAR T cell, the genetic sequence of the aforementioned antibodies must be introduced into the host’s T cells. Not only that: it must be introduced into a specific location, so that the T cell will express this antibody as a cell-surface protein, effectively replacing its T cell receptor with the new, artificial antibody-based receptor. A variety of genetic engineering techniques can be used to create these transgenic cells, including CRISPR and specialized transgenic viruses.

Once the cells have been so altered, they can be tested for effectiveness, cultured in large quantities, and given to the host intravenously. Often, the host is prepared with low-dose chemotherapy to reduce the concentration of their own remaining T cells, to allow the chimeric antigen receptor T cells to monopolize the attention of the rest of the host’s immune system and to enhance the chances of a large-scale encounter between the CAR T cells and the cancer.

If the therapy is successful, the chimeric T cells not only attack the cancer exactly as they have been engineered to do, but they encourage the rest of the immune system to join in, even if the cancer had previously concealed itself. The chimeric T cells thereafter multiply within the host indefinitely as any other T cell line would—now a permanent part of the host’s cellular makeup.

This therapy presents one major side effect. Having such an overwhelming proportion of one’s white blood cells be of a specific line that is attacking a single pathogen with great vigor is unusual, and the cytokine signals secreted by those white blood cells can, as a result, become excessive and dangerous. This is called “cytokine release syndrome” and involves the body responding to the chimeric cells’ activities with a dangerously high fever and other signs of an immune response to a serious infection. Although the onset of cytokine release syndrome is a sign that the CAR T cell treatment is working, it must itself be managed with steroids and other immunosuppressive remedies.

Stay tuned for more in this blog series or if you need to access I-O resources now, like this immuno-oncology guidebook, visit our one-stop Immuno-oncology Hub.

For Research Use Only. Not for use in diagnostic procedures.

Leave a Reply